Published in the

For once, Indian Armed Forces is ahead of the technology curve. Let's cash in on it.

26 September, 2022 12:33 pm IST

The Russia-Ukraine War has seen not just big guns but also rockets and missiles with longer ranges. The war has also taught us that flexible weapons systems like the USA’s high mobility artillery rocket system, or HIMARS, have a great effect on the battlefield. If transposed to the Himalayan terrain, it would put the Indian Army in a dilemma.

The Himalayas on the Tibetan side are relatively flat and stable. Heavy weapons systems of China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) with their longer ranges reach deep into Indian territory with impunity. Hence the PLA lays a lot of emphasis on long-range rocket systems and flaunts them. On the Indian side, the Himalayan terrain is steep and restrictive with limited mobility. Resultantly, the deployment of heavy weapons with longer ranges poses problems. Terrain limitations preclude any attempts to match the PLA on a weapon-to-weapon basis. This places India at a huge disadvantage. To offset this factor, one has to be forward-looking and adopt futuristic technologies.

Ramjet technology

Fundamentally, if India cannot get longer-range equipment up in the Himalayas, then it needs to extend the ranges of its existing artillery systems. Prima facie, it is easier said than done.

However, we are at a stage when we can make it happen through Ramjet technology. In the case of rockets, incorporating Ramjet is a natural extension of existing rocket motors. In the case of guns, it is a little more complicated.

The range of a gun or rocket can be extended by increasing the amount of propellant. Ranges of guns can also be extended by increasing the barrel length. However, any range extension by increasing propellant quantity or barrel length comes with an unacceptable penalty of stability, weight, mobility and deployability. All these factors increase geometrically as propellant quantity or barrel length are increased.

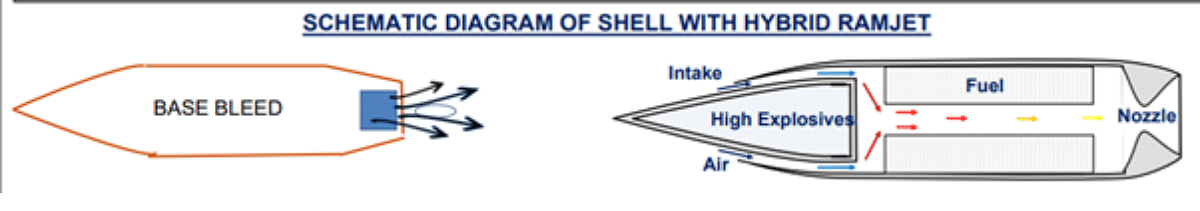

Both these methods have also reached their maximum battlefield limits for a given weapons system. In the case of guns, aerodynamically streamlined shells using rocket assistance/base bleed technologies provided partial answers by extending ranges by 25 per cent. However, even these technologies have reached their upper limits. The range ceiling can be broken through Ramjet technology only. Adapting the Ramjet technology into a gun projectile is a complicated process. Fitting it into a rocket is easier.

A Ramjet is an extended version of a rocket-assisted projectile. The schematic diagram of a shell with a hybrid Ramjet is shown above. Unlike a traditional rocket motor, the Ramjet is an air-breathing engine. It carries a fuel-rich propellant and ingests air from the atmosphere as an oxidiser. As the shell moves forward, air is taken in from the inlet and gets compressed. The compressed air is rammed onto the combustion chamber where it interacts with the propellant to produce high-temperature gases. However, for such combustion to happen the shell must be accelerated to a velocity of Mach 1 plus for the air to get rammed into the engine (combustion chamber) at high pressure. The combustion products are then expelled through a nozzle to produce thrust. Luckily, in the case of an artillery gun, the initial muzzle velocity of the shell is high enough to get the Ramjet going. When compared to the rocket-assisted /base bleed projectile, it is possible to increase the range by 100 per cent using Ramjet engines.

Indigenous research has indicated that a 155 mm shell, which would have ranged 24 kilometres, has the capacity to range up to 40-45 km using a Ramjet (in plains). In high altitudes, this will get enhanced by at least 25 per cent more. Hence an overall range far more than 50 km is very much on the cards. A conservative and approximate trajectory is shown in the graph below. When these trajectories are transposed to actual gun systems in service, the ranges which are likely to be achieved can go up to 70 km. However, there are implications of this increase in range. These pertain to meteorology, accuracy, target acquisition, lethality, and cost. These need to be factored in and development must take place accordingly.

At ranges more than 30 km, the effect of meteorology will be pronounced. The shell could land as far as 500 metres away from the target, making it ineffective. Hence, some form of guidance needs to be incorporated into the shell. The guidance could be in the form of a Precision Guidance Kit or a full guidance system like in the Excalibur ammunition. The alternative is to track the shell through a Weapon Locating Radar (WLR) and then direct the shell onto the target. Alternatively, a Datum can be established with the WLR.

The third and more practical and cost-effective option is to develop a pilot projectile with ballistics identical to the Ramjet projectile. In place of the high explosive content, the shell can have a GPS with a communication system which transmits its location constantly back to the gun position. In such a case, the trajectory of the shell is clearly known, the point of impact identified, and a correction plotted. Actual shells with High Explosive content can then be fired on corrected data. All these options need to be explored concurrently.

However, the basic question is how far has Ramjet technology progressed to fit it into a shell? The answer is that it has come quite far. NAMMO, a Norwegian firm has designed a Ramjet projectile. The projectile is essentially a 105mm shell with a 155mm shroud around it. The space between the basic 105 mm shell and the 155mm shroud is used for the air intake of the Ramjet. The shell has been fired and the Ramjet technology in a gun system has been proven recently. In this design, the lethality of the shell will be far less than the normal 155 mm shell. This is one of the disadvantages of the Ramjet projectile. It also implies that there is a very high degree of target acquisition and accuracy of fire required to make this shell effective at the target end. In case the lethality of a 155MM shell is to be retained, certain other innovative methods must be thought of for the air intake of the Ramjet projectile.

Adequate work has been undertaken indigenously to design a Ramjet projectile at the behest of the Indian Army. The project is progressing satisfactorily. When this projectile is proven, it will put us at par with international efforts in time and space. In terms of costs, we will get it at a pittance. The great opportunity is that the technology developed for guns can be ported to rockets with huge outcomes.

The case for rockets

The USA supplied HIMARS to Ukraine. It has been used to good effect in the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict and has been critical in restoring the firepower balance to give Ukraine a fighting chance. Everyone is going gaga over the HIMARS. It is a missile launcher mounted on a five-tonne truck which can fire six guided missiles in quick succession. The current range of 80 km is roughly similar to that of the unguided Russian Smerch missiles.

However, the HIMARS with a GPS-guided missile is way more accurate. It is almost pinpoint accurate when used against fixed targets. HIMARS can also fire a single Army Tactical Missile System missile, which has a range of 300 km. In effect, a variety of rockets can be fired from the same launcher.

In the Ukrainian war, HIMARS has been used for interdiction, isolation, destruction, degradation and denial. The Indian equivalent of this system is the Pinaka. Long back I had written about the value of Pinaka in conventional non-contact deterrence. However, the Ukrainian war indicates that we need a longer version of a Pinaka. That is where the Ramjet technology developed for 155 mm shells comes in.

Extending Pinaka range

The Pinaka Mark 1 has a propellant of vintage technology which gives a range of up to 37 km. When case bonded propellants were developed and introduced, the range went up to about 55 km. However, being unguided, it was very inaccurate. Hence the guided version was developed. With aerodynamic control and guidance, a range of up to 80 km has been achieved with a great degree of accuracy. This version is now being introduced in the Army.

However, in the Chinese-Indian operational context, it is inadequate. Introducing a new system with longer ranges is time-consuming, costly and has geopolitical ramifications of being mistaken for a nuclear-tipped system. Moreover, a heavy system with extensive ground support equipment will not be able to operate in the mountains. Hence the logical way forward is to incorporate a Ramjet engine and extend the range of the existing guided Pinaka.

A Ramjet engine will extend the range to 250 km without breaking a sweat. From there to proceed to a hypersonic missile is the next logical step. The Pinaka has a calibre of 210 mm which is more than adequate to achieve the desired lethality. In effect, India needs to have different rocket/missile variants which can be fired from the same launcher for different purposes like in the HIMARS. The best part is that India has the technologies to achieve it. Once a range of 250 km is achieved, it will also offset any shortages or delays in inducting fighter aircraft-based firepower. Incidentally, this is what the PLA is doing—offsetting high altitude-induced shortfall of fighter ac-based firepower with long-range missile power.

Edge over the adversaries

As usual, there is a proviso. Indian Armed Forces have to believe that this is possible. They have to go the full length based on a systems approach to invest in this next-generation technology. Very significantly and creditably, the Indian Army has already invested in the Ramjet technology for 155 mm guns. The results will speak for themselves in due course.

The challenge for the Indian Army is to extend this faith so that Ramjet technology can be ported onto other systems in a parallel mode. The challenge for the Indian Air Force and Indian Navy is to enter this field which they have been loath to do so far. For once, we are ahead of the technology curve. We need to cash in on it. The armed forces have the choice of investing in homegrown technology to have an edge over the adversary today. They also have the choice of not doing so. In that case, they will have to procure this technology at least 10 years later at about X times the cost to match the adversaries’ capabilities.

In the artillery, there is a saying that “Guns do not lie”. They shoot straight and fast. This technology is as fast and straight as an old gunner can shoot. The rest is up to the current crop of military men.

Lt Gen P.R. Shankar (retd) is former DG Artillery and presently professor at the Aerospace department, IIT Madras. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

Comments

Post a Comment